The Manuscripts.

This post begins a serialized translation and commentary of Pliny the Younger’s letters (6.16 and 6.20) to the historian Tacitus about the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79. This was the disaster that buried Pompeii, Herculaneum, and other sites. These posts are part of a book project that intends to understand the scholarly and popular reception of those letters. I am teaching these letters for LAT 223 at DePauw in Fall 2012; it’s a good time to start.

I will provide the Latin (using Mynors’ 1963 Oxford Classical Text [OCT]), and then work through it with a translation, dissection of grammatical constructions, and discussion of what the letters tell us. I will doubtless make mistakes as I proceed, and will be grateful for comments and corrections; the essence of scholarship is rectification through better evidence, arguments, or questions.

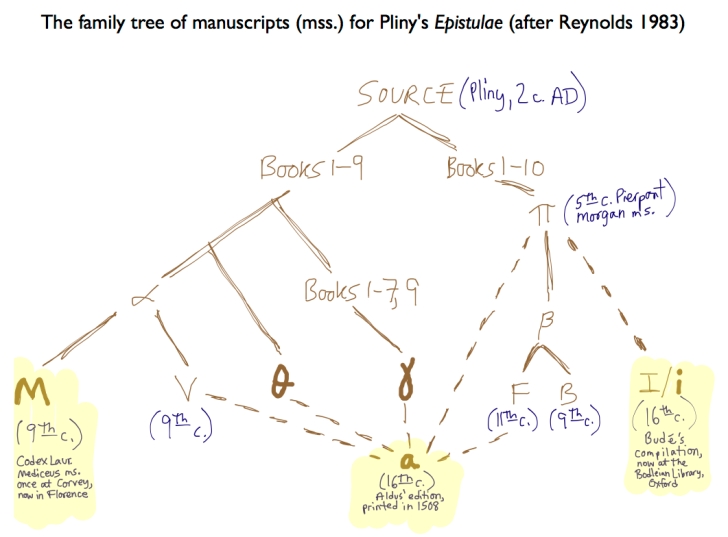

Today we start with how we even have these letters: the manuscript tradition. Simply put, we do not possess the Younger Pliny’s original letters. What we do have are later copies of, or excerpts from, compilations of his letters into books and collections. These copies fall into groups, or ‘traditions’, as reconstructed through textual criticism. (Below are just the basics; for more detail, see Roger Pearse’s site, which works from L. D. Reynolds, Texts and Transmission, Oxford 1983, 316-22, which in turn relies upon Mynors’ 1963 OCT. William Johnson at the University of Cincinnati also has a useful bibliography for Pliny). Note: the abbreviation ‘ms.’ = ‘manuscript’ (‘mss.’ = ‘manuscripts’).

- The ‘Nine-Book’ series

- The ‘Eight-Book’ series (known as ‘γ‘ [gamma]):

- Codex Veronensis deperditus (‘lost’) (at least 10th c. AD); contained books 1-7 and 9, with some omissions from books 1 and 9.

- Oxford, Holkham Hall 396 (15th c.), contains 167 letters of the γ tradition.

- Supplementary source (known as ‘θ‘ [theta]), date and origin uncertain, represented by several manuscripts in the Vatican, Turin, and Paris, used to fill in gaps and offer better readings in certain places.

- Carolingian source (known as ‘α‘ [alpha]):

- ‘V‘: Codex Vaticanus latinus 3864 (9th c. AD), contains books 1-4;

- ‘M‘: Codex Laurentianus Mediceus, Pluteus 47.36 (9th c. AD), contains books 1-9.15, 9.17-9.25; written at Fulda monastery; was at Corvey monastery before it was stolen and brought down to Italy; it is now in Florence, in the library of the Medici family. Links to digital photographs of the letters: 6.16 (p.180) and 6.20 (p. 186).

- excerpt in Codex Vaticanus latinus Reginensis 251, pp. 11-13 (early 9th c. AD), containing letter 6.16.

- The ‘Eight-Book’ series (known as ‘γ‘ [gamma]):

- The ‘Ten-Book’ series (known as ‘β‘ [beta]):

- ‘Π‘: Pierpont Morgan M.462 (late 5th c. AD), contains 2.20.13 to 3.5.4; once whole when in the collection of St. Victor in Paris from the 14th-16th c. Only six leaves remain, but all other manuscripts in this series were copied from this one. This publication is available as a Project Gutenberg e-book, with scans of the plates if you want to see what an ancient text looks like!

- ‘B‘: Florence, Laurentianus Ashburnham 98 (9th c. AD), contains Book 1 down to 5.6.31, minus a couple of letters in books 2 and 3, a descendant of Π.

- ‘F‘: Florence, Laurentianus S. Marco 284 (11th c. AD), contains Book 1 down to 5.6 (exactly 100 letters), a descendant of Π.

- ‘I/i‘: Oxford, Bodleian Auct L.4.3 (a compilation of the 16th c. by G. Budé and containing all the letters), largely relying upon Π.

- ‘a‘: editio Aldina 1508 (a printing-press edition), containing all the letters.

Our letters (6.16 and 6.20) happen to be extant in multiple manuscripts. This is good, because we have multiple sources that we can compare towards trying to get as close as possible to Pliny’s original text. This is also bad, because it can lead to confusion, contradiction, and uncertainty, esp. regarding points such as the month and date of the Vesuvian eruption. Mostly it’s good; we’d rather have more sources than fewer.

As the list of series and sources above can be confusing, here’s a graphical representation of how the Younger Pliny’s letters have descended to us:

For letters 6.16 and 6.20, the principal relevant sources are: γ, θ, M, i, a, which offer variant readings for particular passages. Mostly, it is three documents surviving physically today (M, a, i) that provide the OCT text from which we will be translating; I’ve highlighted those in yellow. When it is important for a point of understanding or interpretation, I will refer to these sources to provide alternate readings. The whole set of alternate readings for any text is called an apparatus criticus, and the ‘ap crit,’ as it is known, appears at the bottom of each page of text in modern scholarly editions, wrapped in mystical abbreviations and orthography that are revealed to graduate students with great solemnity, as if it’s some secret about the authorial certitude of our literary heritage (and it sort of is); here’s a key to unlock the ‘ap crit’ abbreviations.

The scholarly edition of the Latin text for this translation project, as mentioned above, will be the Oxford Classical Text edited by R.A.B. Mynors and published in 1963. In our next post, ‘Dramatis Personae,’ we will learn about the characters in this story, and begin to find out why the Younger Pliny, some 25-30 years after Vesuvius exploded, wrote these letters in the first place.

Thanks for this excellent post backgrounding the mss. of pliny’s letters and the ms. traditions. I’ve just been delving (last night, in fact) into the background of the Greek Magical Papyris (so-called PGM) and roundly agree with your assessment of fn’s as “…wrapped in mystical abbreviations and orthography that are revealed to graduate students with great solemnity, as if it’s some secret about the authorial certitude of our literary heritage (and it sort of is).” Indeed. Mystic languages in and of themselves, imparted by learned scholars and others.

As well, I’ve a little project reviewing some of pliny’s references on animals – specifically, African animals, – and so your work is most timely for me and I look forward to its continuance!

(And as you noted, I’ve also – deliberately – used a few ‘mystical abbreviations’, though I think somewhat more open…

Thanks! the PGM are fascinating. Makes me think of instances of deliberate obscurity or obfuscation in ancient writing (when, after all, writing in the ancient world was itself indecipherable to most people), so adding extra veils over the letters begins to turn the textual tradition into a kind of game for hierophants.

Induction to the educated elite was signified by knowing Greek and Latin well into the 20th c. I suspect that, like much of the apparatus of the old aristocracy, this practice of linguistic competency (and conceit) was mortally wounded in the Great War.

yes, and of course with christianity in the Nile valley, and the harassment of traditional religion and magic, the latter simply went underground – and the tradition of obscurity has, (I think unfortunately) continued into the twentieth century and beyond. In graduate school, my professors both in egyptology and classical arabic would counter my more analytical ques. with quips about these topics not being in the philological tradition. Perhaps the web is helping to open upthese issues.

Thinking of using an introductory chapter from Betz’ compilation of the PGM for a universary course I’ll be teaching here in Burundi, it quickly became clear there were simply to many unknowns – esp. for students having english as a second language.

I deeply regret not having been able to follow my interests (went on in anthropology, in frustration). Though in my blog, I do try to open aspects of ancient (and modern) obscureae in ways less obscure, to intellegent readers.

Peter Brown, whom I had the great pleasure to know and engage with while working in Egypt some time ago, has always represented to me a way to get out of the maize of ‘only philology matters’ (or etc). A. Leo Oppenheim, former mesopotamian scholar at Chicago, also possessed such open attributes and I happily worked with him just before his death during his sabbatical at Berkeley.

BTW – I also very much appreciated your geneology of ‘Pliny’s family tree’ – a similar (though not updated, as far as I know) tree has been developed for the bestaries – out of physiologus, etc sources – do you now of more recent (last 20 years efforts in that direction)?

Merci, and good work.